Sometime in the 1990s the Foodgrains Bank became aware that working to end global hunger would need to include changes to some government policies. Was there anything we could do?

The first problem was the difficulty of buying food close to the communities we serve to reduce shipping costs. The Canadian government only allowed 10 percent of their food aid money to be used for this purpose.

Small-scale farmers in developing countries were complaining they couldn’t compete with subsidized exports from rich countries.

So in 1996, we started trying to change this policy. It was only after the huge protest by small-scale farmers at the Seattle World Trade Organization’s meeting in 1999 that the Foodgrains Bank created a department to try to change some government policies in Canada and internationally.

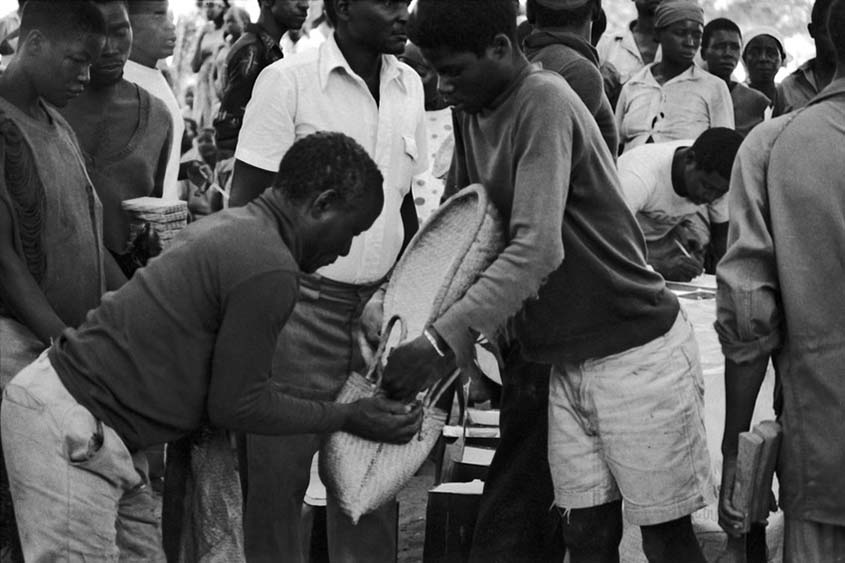

A Mennonite Central Committee corn distribution in Mozambique in 1985. (Photo: Jim Shenk)

To increase our efforts, we sought allies in Canada, the US and Europe by establishing the Canadian Food Security Policy Group and the Trans-Atlantic Food Assistance Dialogue.

These activities yielded fruit – first by changing and eventually eliminating the Canadian local purchase restriction and later by assisting with the renewal of the international treaty that deals with food aid.

Over the years, many international partners began to point to climate change as an increasingly important cause of global hunger. We’ve advocated that the Canadian government increase its support for small-scale farmers in developing countries and help them adapt to climate change. We played a significant role in Canada’s decision in 2009 to double aid for agriculture and to make food security one of its aid priorities.

In 2017, when all the existing aid priorities were replaced by the Feminist International Assistance Policy, which hardly mentioned food, we produced evidence that working with food producers was relevant to several of the goals named in the new policy. This included empowerment of women, economic growth and climate action.

As a hunger-fighting organization, we could not ignore the impact of climate change on hunger, but needed to find a niche where we could work for policy improvements while navigating strong differences of opinion among our constituents, the Canadian public and within government. That turned out to be climate finance – the money Canada contributes to developing countries to help them adapt to climate change – and Foodgrains Bank quickly became a leading voice on this issue. One of our staff members, Naomi Johnson (pictured below), was named one of Canada’s best Young Impact Leaders in 2022 for her success in this policy area.

Canadian Foodgrains Bank senior policy advisor Naomi Johnson was recognized in 2022 for her success working on the issue of climate change impacts on global poverty and hunger.

The public policy work carried out by the Foodgrains Bank supplements our direct program work in developing countries by increasing the dollars and improving the quality of Canada’s aid. The Canadian government sees value in this and continues to support policy dialogue through its core grant to the Foodgrains Bank.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2023 edition of Breaking Bread. Download your copy here.