The lingering effects of the pandemic and the global hunger crisis have led to incredibly high costs of food, making food less affordable for people experiencing hunger. They have also created challenges for organizations like Foodgrains Bank who are responding to growing hunger needs.

In recent years, supply chain disruptions have become common. In several countries, for example, it became challenging to purchase cooking oil immediately after the invasion of Ukraine. In East Africa, it has been difficult to purchase red beans this year, a product commonly provided in food distributions, due to poor harvests. Partners adapted their programming to provide mung beans as a substitute.

In most cases, Foodgrains Bank works with our members and local partners to purchase the food and the partner then distributes it. Our procurement work has given us a unique vantage point on rising food prices around the world.

Food parcels look different in each country, even sometimes between communities, as they are determined by what is culturally appropriate. In South Sudan, for example, a typical food parcel includes a cereal (usually sorghum), beans, and cooking oil. In Syria, the boxes include items like rice, pasta, canned meat, lentils, sugar, oil, tomato paste and tea.

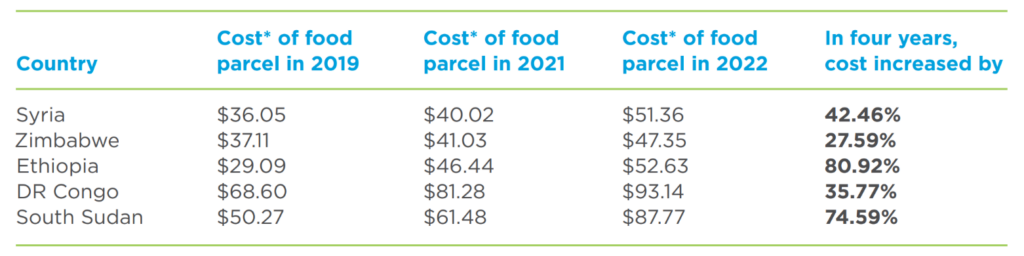

The table below gives a snapshot of the price of food that we purchased from 2019 (pre-pandemic) to 2022. Across the board, prices have risen dramatically.

*Prices are listed in USD. Food parcel contracts are in USD and payments made upon delivery, therefore Canadian dollar amounts depend on exchange rate at the time of delivery. In Syria, the typical food parcel was simplified between 2019 and 2022 to reduce costs, which still went up by over 42%.

As food prices go up, there is greater need for assistance. But as those prices go up, it is also harder to provide assistance. Partners are forced to make difficult decisions about how many people they can reach and with how much assistance.

Heartbreaking trade-offs are a reality of what it looks like for partners when they are serving people in the midst of a hunger crisis impacted daily by high levels of inflation and economic instability.

Pentecostal Assemblies of Zimbabwe, local partner of member ERDO, reported that “food availability in households is a challenge due to the continuous ailing economy and high inflation in the local currency.”

And as the landscape of humanitarian assistance changes with the influence of these factors, we continue look to our members and local partners for their expertise on how they can adapt to best meet the needs of the people they’re serving.

In the past, all of the assistance provided by Foodgrains Bank was provided as “in-kind” food – giving people a collection of food items. Much of our assistance remains in-kind, but we now use a variety of methods to provide assistance. In some cases we provide cash, so that people can purchase the food they want. In other cases we use vouchers to local grocery stores or markets, which enable people to purchase food.

These sorts of food assistance have been seen to be beneficial because they support the local economy, while also providing continued independence and freedom of choice for people who are living in the confines of poverty, often through a crisis.

Every time a partner plans a new project, they conduct an assessment to determine what kind of assistance is most appropriate. This includes asking people who will receive the assistance what kind of assistance they would prefer.

Given the economic uncertainty and inflation experienced in many parts of the world, local partners implementing cash or voucher assistance realized some program participants desired in-kind food assistance as a dependable form of support.

“People are worried when they go to the markets with their cash, they might not be able to access the food they need anymore, or that it will be too expensive for them to buy,” says Epp-Koop. “The uncertainty that people are facing helps drive interest for in-kind assistance as people see it as more secure.”

That isn’t to say that there aren’t advantages to cash assistance. People receiving cash have the choice of how to use it so they aren’t limited to what is provided in a set food basket, and can purchase the food they believe is best for their family.

Rising food prices also have an impact on the amount of cash sent to participants. Typically, the cash or voucher amount is set to purchase a certain amount of food or a certain percentage of what’s known as the Minimum Expenditure Basket. If items cost more, cash transfers need to get larger. In some cases, transfer values were adjusted every month to reflect rapid inflation.

Our partners are also learning about different ways to do cash programming. For example, approximately 40% of our cash projects this year sent cash straight to participants’ cell phone rather than handing out actual cash.

“I have visited participants who really appreciated receiving cash on their phone,” said Epp-Koop. “People liked that it is safe, secure, convenient, and confidential. And in many parts of the world, cellphones are very common.”

As a network, Canadian Foodgrains Bank, our members and partners are committed to consistently evaluating the context of where we’re serving to ensure our programming is most effective and reaches people currently living with food security.